Criminals are getting smarter. So should you.

Consumer Reports Magazine: January 2012

Illustration by: Stuart Bradford

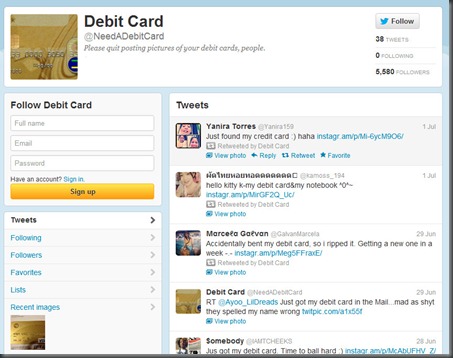

More than half of U.S. adults have six or more password-protected accounts online, our latest survey shows. Who can remember the passwords? You try by keeping them short and sweet: your pet’s name and “123.†You use the same one for multiple accounts. And you keep them in your wallet for easy access.

You’re not alone. In our survey, 32 percent of respondents used a personal reference in their passwords, almost 20 percent used the same password for more than five accounts, and 23 percent kept a written list of passwords in an insecure place. The national survey of 1,000 adults was conducted in October by the Consumer Reports National Research Center.

Trouble is, such practices expose you to the kinds of attacks that today’s hackers have been launching against websites. When hackers get your passwords, they gain access to your accounts.

It doesn’t have to be that way. Read on to learn the best and worst types of passwords, how to create strong ones, where to store them for safekeeping, and—better yet—how to remember them.

A growing threat

Your chances of having a password stolen on a given day are probably slim, but the risk is real and growing. To understand why, you need to know how today’s hacker works. No, he doesn’t sit in a basement, attempting to sign into your account by pounding away at a keyboard until he stumbles upon your password. Most likely, he breaks into an insecure website that has many passwords on file, including yours. Then he finds out many of those passwords using highly sophisticated password-cracking software and a souped-up computer. Here are some of the most troubling developments we’ve discovered:

Poor website security. It’s widespread. According to the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse’s chronology of data breaches, more than 312 million data records were exposed over the past six years by hackers breaking into sites. (Not all records included passwords.) In a study of more than 3,000 sites published last winter by Whitehat Security, a California-based firm that helps companies protect sites, most were exposed to a serious security vulnerability every single day of 2010. Banking and health care sites performed the best; retail and financial-service sites performed below the overall average.

One in seven sites studied were vulnerable to a prevalent attack known as SQL injection, in which the hacker penetrates an organization’s computer by tricking it into executing the hacker’s own programming instructions. SQL injection was used to hack into the Sony Pictures site last year, as well as into the sites of Nokia, Heartland Payment Systems, and Lady Gaga, according to the September 2011 Monthly Trend Report by Imperva, a California-based security firm that helps companies prevent data breaches.

Once a site has been hacked, the main safeguard of any user passwords it houses is how securely those passwords are stored. Some sites use storage that’s less secure than it should be. Sony Pictures, for example, stored its users’ passwords in readable form. Security professionals refer to that as plain text, which provides no obstacle to hackers.

Many reputable sites use a secure storage technique known as hashing, which makes hackers work to convert the stolen data into usable passwords. According to experts we spoke with, the average consumer can’t tell how securely their password is stored on a given site. But using the strongest password gives you the best chance of resisting some attacks.

Lower hacking costs. The kind of hardware used to crack passwords has plunged in price. According to Robert Imhoff-Dousharm, information security officer at SanDisk, for $3,000 you can buy a PC with the password-cracking power of the fastest supercomputer in 1994, which cost $30 million then. A PC with that power can be assembled from parts you can buy from a computer retailer, and it can crack any eight-character password in just 23 hours, he says. Have a tighter budget but more time? No problem. An $800 starter version can do it in 40 days.

Better hacking tools. The power of password-cracking tools has surged. The key technology is the same speedy graphics card, also known as a graphics processing unit (GPU), that personal computers use to speed up action games.

The latest GPUs are also ideally suited for password-cracking software, Imhoff-Dousharm explains. “GPU technology has advanced so quickly, and password crackers have taken advantage of it to the point where pretty soon nine characters won’t be usable anymore,†he says. It’s fairly easy to find free software online that can crack passwords. John the Ripper, a popular program available from security expert Alexander Peslyak, is intended for legitimate security testing. And Cain & Abel, offered by security consultant Massimiliano Montoro, is a password-recovery tool. But those programs can also be used for illegal password cracking.

More potential hackers. With hardware so cheap and powerful software readily available, it’s no surprise that many people have recently taken to password cracking as a hobby, if not an occupation. According to Imhoff-Dousharm, the size of the online community that exchanges tips about the four most popular cracking utilities and the latest GPUs has skyrocketed from a couple of thousand people three years ago to more than 80,000 today.

There’s growing evidence that criminals have begun taking advantage of all those trends in a significant way. Two consumer sites, Gawker.com and Sony Pictures, experienced data breaches in the past year, exposing millions of consumers’ passwords to hackers. If those passwords were also used for other accounts, then hackers had access to them, too. In October the FBI arrested a man for hacking into the e-mail accounts of 50 people, including actress Scarlett Johansson and singer Christina Aguilera. He told authorities that he had guessed Johansson’s password by mining publicly available data and social networks for personal information about her.

The 2011 Consumer Reports State of the Net survey, published in June, projected that 3.7 million online U.S. households had been notified in the past year by a company, organization, or the government that their personal information had been lost, stolen, or hacked. The same survey also projected that the Facebook log-in information and accounts of almost 1 million members had been used for unauthorized purposes in the past year.

Of course, no matter how secure your passwords, you still have to be vigilant about other ways unauthorized people can gain access to your accounts.

Phishing sites, for example, are fraudulent sites that use official-looking e-mail to lure victims, posing as a bank or other familiar institution. Once you have entered your ID and password or PIN, the phisher can use them to steal from your account. The 2011 Consumer Reports State of the Net survey projected that approximately 6.4 million online users had in the previous year submitted personal information in response to an e-mail linking to such a site.

Then there are keyloggers. That malicious software, which stealthily captures and discloses your keystrokes, can be planted on your computer online if it gets hacked or by someone with physical access to it. Security software might be able to detect a keylogger. Anti-keylogger utilities are also available online, though we haven’t tested them. A keylogging device (about the size of a battery) can also be attached to your keyboard’s cable.

You still must watch your own practices. If you disclose a password to someone you don’t personally know and trust, or if you write it down but don’t secure the written version, you have exposed your account to unauthorized access.

Consumer Reports Magazine: January 2012

3.7 million online U.S. households had been notified in the past year that their personal information had been lost, stolen, or hacked.

Best ways to protect passwords

Here are the most important password-protection measures that experts recommend to keep hackers at bay:

Don’t use the same one twice. If a hacker obtains a password you use from one site, he’ll have access to your other accounts. To make passwords easier to remember, it’s OK to use a similar character pattern from site to site, varying part of it in a way that’s intuitive to you but not obvious to anyone else.

Make them strong. Our survey found that 29 percent of people who use passwords on their most sensitive accounts use one with seven or fewer characters. That’s too short. Use at least eight characters. Include an uppercase and a lowercase letter, plus a digit and a special character. That will better protect you from someone guessing it, and it also helps when the password is stored at a site that uses hashing as the security technique.

Making a password longer also helps when it’s protected by hashing. Using a hash-cracking-time spreadsheet developed by Imhoff-Dousharm, we estimate that it would typically take a $2,000 computer 2½ hours to crack the strongest seven-character password. An eight-character password would hold up for about 10 days, and a nine-character password would last for approximately two and a half years.

Avoid the obvious. Hackers have extensive dictionaries of widely used passwords. When you’re composing a password, don’t use common words, names, or facts from your life that are likely to be in such a dictionary or that someone might guess or find out (e.g. birth date, child’s name). Avoid predictable patterns, such as starting with an uppercase letter.

Keep them safe and up-to-date. Don’t write down full passwords. But if you must, keep them under lock and key. Based on our survey results, we project that 34 million adults keep a list of passwords or clues in a place that might be insecure.

Experts told us they stored their lists on an encrypted flash drive, used an online service such as LastPass (www.lastpass.com), or stored them encrypted on a computer using KeePass (www.keepass.info), a data-protection application. Hackers can be quite skilled at conning people into disclosing their passwords. Don’t give passwords to anyone over the phone, via e-mail, or through a social network.

If you have an old password, it may once have been strong enough but now may be too weak for today’s hackers. Consider replacing it with a stronger one.

Secure your computer and browser. Keyloggers and other malware are a real risk, especially on publicly accessible computers. Keep your operating system and major applications up-to-date. Run an effective security software suite that automatically updates itself. (For brand-name Ratings, see our June 2011 issue.)

When browsing a password-protected website, look for “https:†in the site’s address. Sign into accounts by typing the URL into your browser, not by clicking on a link in an e-mail; the link could take you to a fake site.

Toward better security

The job of protecting passwords can’t rest entirely with consumers. Until more website owners improve security, hackers will keep stealing passwords. Owners should reduce their vulnerability to SQL injection, which has accounted for 83 percent of successful hacking-related data breaches since 2005, according to Imperva’s September 2011 Monthly Trend Report.

Ed Skoudis, an instructor at the SANS Institute in Washington, D.C., which trains security professionals, has observed many data breaches. “SQL vulnerabilities are rampant,†he says. “SQL injection was a major factor in the cases we were working on 10 years ago. It’s depressing that it still remains a major factor today.â€

Experts also say that sites should store consumer data securely using hashing or even better, using strong encryption. Publicly held corporations and companies that process credit cards are supposed to follow industry standards for safeguarding data.

But even a well-known site could outsource its data handling to a company whose practices you don’t know. For example, Verizon, Walgreens, and other major brands had to warn millions of consumers last spring about possible e-mail scams when Epsilon Data Management, the Dallas-based e-mail marketing firm for those companies, suffered a huge breach of customer e-mail addresses.

Another security approach is two-factor authentication—the user provides information other than a password that a hacker can’t obtain. For example, Google and Face-book offer a feature that requires you to get a verification code via telephone before you sign in. (On Facebook, click on Account Settings, then on Security, and then on Login Approvals.) A variation on that uses biometric data, such as from a fingerprint. Two-factor is not perfect, but it is better than using passwords alone.